Making sense of binary

Growing up, I never thought I’d be the type of person to gush over 1’s and 0’s. I always assumed that numbers were the dull sidekicks to more creative pursuits. I was busy writing short stories about ancient gods in dusty corners of my home. But ironically, these short stories were stored on digital hard drives—under the hood, every word and punctuation was represented in binary. It took me far too long to realize just how magical that is.

Binary has a sneaky way of showing up in every piece of technology we use. Godot 4 is no exception. Not only do we have magical scene trees, signals, and animations, but beneath the hood, we still rely on the simplest building blocks in computing: on/off signals, otherwise known as bits.

Why Binary is Everywhere

In essence, digital computers store and process data using two states, often represented by 5V and 0V. By “5V”, we just mean a higher electrical voltage (sometimes 3.3V on modern circuits, but the idea is the same), and by “0V” we mean ground or no voltage.

Because it’s simpler for hardware engineers to detect only two stable voltages—high and low—most digital circuits choose this binary approach over juggling infinitely many voltage levels. Each 5V signal (sometimes called “logic high” or “1”) and 0V signal (“logic low” or “0”) flows through transistors and logic gates, enabling the CPU to carry out all of its operations. Under the hood, everything from storing a single character of text to rendering a full 3D scene in Godot 4 is essentially just flipping these high/low states at incredible speeds.

Binary underpins all digital computing: these two electrical states—on/off, high/low—are all the hardware needs to create the building blocks of modern computing. Once you understand that hardware likes this simplicity, it becomes clearer why we represent data in bits and bitmasks, and why we keep bumping into \(2^n\) patterns in everything from memory addresses to collision layers in Godot. Understanding binary is like learning the secret handshake of all modern computing.

Quick Math: Powers of Two

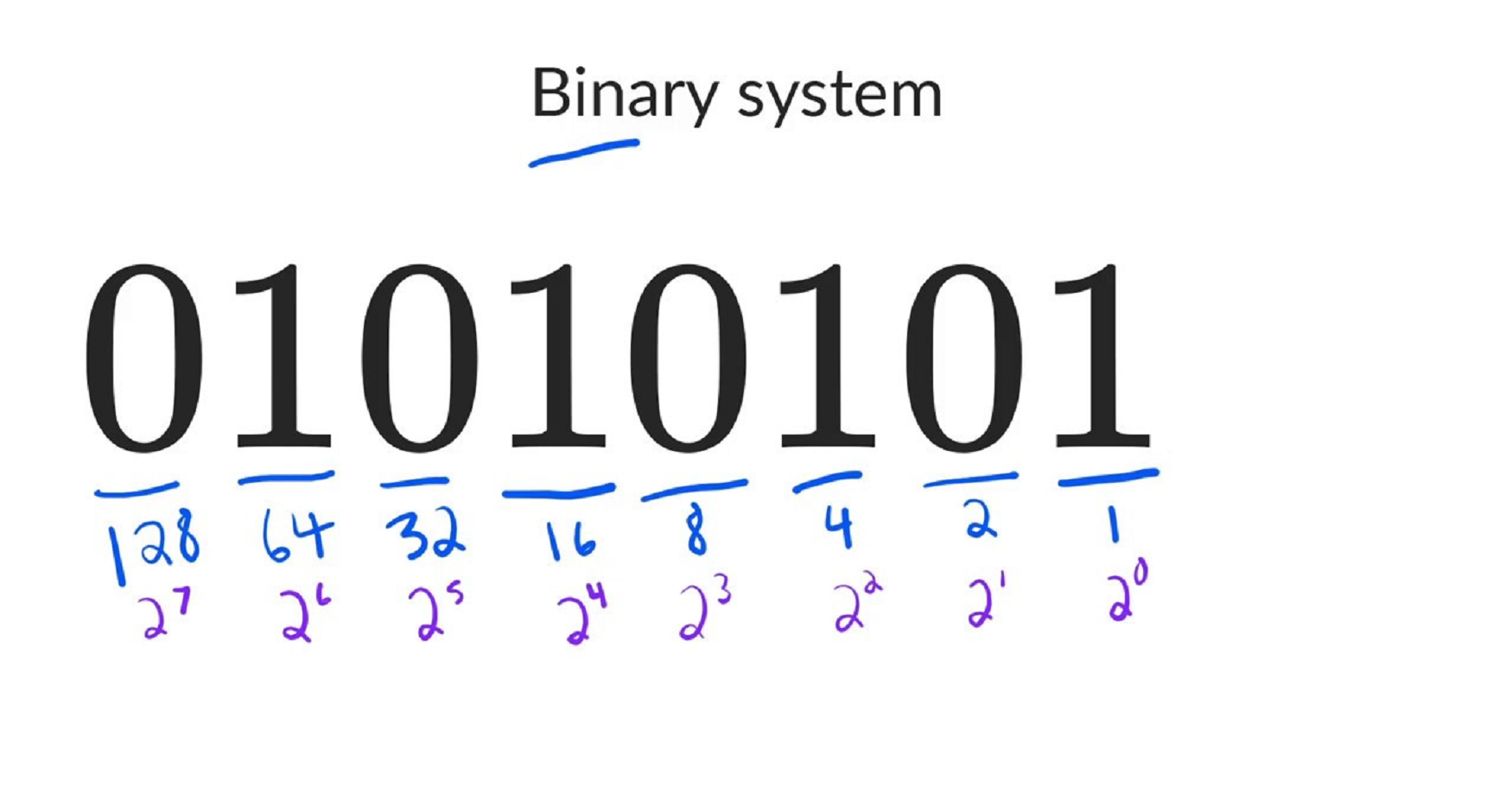

A bit can be 0 or 1. With one bit, you have $2^1 = 2$ possibilities. With two bits, $2^2 = 4$ possibilities.

To see where the powers come from, it helps to imagine all possible combinations of bits:

- One bit (0 or 1) clearly has \(2\) possibilities because it can be either 0 or 1. In other words, \(2 \text { possibilities} = 2^\text{1 bit} = 2.\)

- Two bits can be 00, 01, 10, or 11—that’s \(4\) possible patterns: \(2 \times 2 = 2^2 = 4.\)

- Three bits can be 000, 001, 010, 011, 100, 101, 110, or 111—which is \(8\) possible patterns: \(2 \times 2 \times 2 = 2^3 = 8.\)

Generalizing, if you have (n) bits, then each new bit doubles the number of possible patterns. That multiplication of 2 repeated \(n\) times is \(2^n\). So the total number of unique ways to flip those (n) bits on or off is: \(2^n.\)

Keep going, and with $n$ bits you have:

\(2^n\) possibilities.

So if you see a weird number like 512 or 1024 in computing, it’s likely because:

\(1024 = 2^{10}\).

It’s the reason so much in computers looks like a suspiciously round number (in binary), but not in decimal.

Why You Should Care

- Efficient Representation: A single 32-bit integer can hold 32 layers worth of “yes/no” toggles in Godot. Instead of storing 32 separate boolean values, Godot just flips bits on or off.

- Fast Computations: Checking if a bit is on or off is a single bitwise operation—extremely fast on modern CPUs.

- General Understanding: Whether you’re fiddling with collision masks or enum flags, you’ll find references to bitwise logic. Embracing binary, ironically, broadens your computing worldview.

Fancy Math: Summations of Powers of Two

If you enable multiple layers (say layers 1, 2, and 4), you’re effectively adding:

\((2^0) + (2^1) + (2^3) = 1 + 2 + 8 = 11\).

In binary:

\(11_{10} = 0b1011\).

Here, \(11_{10}\) just means the decimal number 11 (the subscript 10 indicates “base 10”). Its binary form is \(1011\), which we write in Godot as 0b1011.

In that binary representation, bits 0, 1, and 3 are set. That’s precisely how your node identifies collisions with any body on layers 1, 2, or 4. And if you ever wonder why your node is ignoring half the collisions, double-check your bitmask. Chances are you’re off by one bit 😉.